1000 Friends of Oregon has often been asked why we’re involved in housing issues. To many, 1000 Friends’ leadership on housing issues seems new — but that’s not the case. There are at least three responses to the question:

- We believe that every community and neighborhood should be welcoming, equitable and climate-friendly for all Oregonians. That means neighborhoods with safe and accessible ways to get to nearby schools, stores, parks, and work — including by walking, transit and bicycling — and with a diversity of housing types to meet the size and financial needs of all Oregon families. Including attached and denser housing options in every neighborhood.

- Housing is a core element of Oregon’s land use program, as reflected in statewide land use Goal 10, Housing.

- 1000 Friends has been engaged in housing issues — including enforcing Goal 10 — since the beginning of the land use program, with the passage of SB 100.

Goal 10 requires that the local land use plans of every town and city:

“encourage the availability of adequate numbers of needed housing units at price ranges and rent levels which are commensurate with the financial capabilities of Oregon households and allow for flexibility of housing location, type and density.”

Betty Nivens was the chair of the State Housing Council when SB 100 passed. Ms. Niven was a leader in crafting Goal 10, and 1000 Friends worked closely with her to ensure that Goal 10 requires all cities to provide residential zoning to meet the housing needs of all Oregonians.

From 1976 on, 1000 Friends devoted all or part of its early newsletters to ensuring that the land use program delivered on the promise of Goal 10. Ms. Nivens reflected on the objectives of Goal 10 in several articles she wrote for the 1000 Friends Newsletter.

“Goal 10-required reforms in local zoning policies can make housing more affordable to more Oregonians. This is achieved by requiring local bodies to change their zoning and subdivision procedures so that local land use policy is sensitive to what people can afford to pay for a house – what might be called ‘income sensitive’ zoning. Hence, local practices which drive up housing costs – such a large lot zoning, higher fees, delays in approval, vague standards, lack of buildable inventories and the like – must be eliminated or modified.

“Oregon is the only state in America to have recognized its responsibility by establishing by establishing state-level policies and a review process which are necessary to chop needlessly higher housing costs out of the local land development process.”

Before there were YIMBYs:

1000 Friends hired its first land use attorney whose focus was Goal 10 and housing in 1977, and we have had staff attorneys and planners focused on housing since then. The first of many housing studies conducted by 1000 Friends was in 1978, in which we studied the 3-county Portland metropolitan region and concluded that the oversupply of zoning for detached, single-family housing was “needlessly driving up the cost … and frustrating the provision of multi-family housing.” Among other things, we called for smaller residential lot sizes and more attached housing options.

The early impact of Goal 10 was remarkable: Within 10 years, the residential capacity of Oregon’s largest metropolitan area more than doubled — without adding an acre of land — but rather through plan and zone changes to meet the actual housing needs of Oregonians, and similar results happened across Oregon.

However, the zoning of our cities has not kept up with the changing needs of Oregon’s families. Family sizes are getting smaller while the populations of those over 65 and of younger families are growing. Compounding the shift in demographics, the cost of housing is outpacing incomes. Our current housing stock does not reflect these changes. This is not an issue of land supply — it’s making sure all our neighborhoods are open to different types of housing, for all families.

According to the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis (OEA), Oregon is short more than 155,000 homes, mostly for middle- and lower-income Oregonians. The OEA calculates that Oregon needs “to build 30,000 new housing units per year” to meet the needs of all. What kind of housing choices do Oregonians need, and what is missing?

As highlighted by a recent AARP report, Making Room: Housing for a Changing America:

“[A]dults living alone account for nearly 30 percent of U.S. households — and that’s a growing phenomenon across all ages and incomes. The housing supply, no matter the locale, has been slow to meet the demands of this burgeoning market or respond to the needs of increasingly varied living arrangements.“

This is just as true across Oregon, where over half the households are made up of 1 or 2 people and yet most residential land is zoned for detached single family housing, leading to unaffordability and lack of choice. Lack of sufficient housing, including diverse market-rate housing, located where people need to live, is also exacerbating homelessness.

The Oregon Office of Economic Analysis explains:

“The problem is in many places one cannot simply build more housing due to zoning restrictions (minimum lot size requirements, setbacks, parking etc). However, if a community were to allow for more units to be built on a given parcel of land, then better affordability can be achieved, and future growth more efficiently accommodated. This is for at least two reasons. First, one would be dividing high land costs over a larger number of units which both lowers cost per unit and increases supply relative to existing zoning. Second, each unit will be smaller than under current zoning, which also lowers the cost per unit.”

How did we get here?

Our towns and cities find themselves in this structural and affordability mismatch for many reasons. One answer is simple neglect: Some land use plans have not been updated for residential zoning since the 1980s.

Further, many single-dwelling housing zones of today were created as a form of exclusion and redlining, a practice used to keep people of color out of the “most desirable” neighborhoods. As summarized by one expert on the subject:

“[S]egregation in every metropolitan area was imposed by racially explicit federal, state and local policy, without which private actions of prejudice or discrimination would not have been very effective. And if we understand that our segregation is a governmentally sponsored system… only then can we begin to remedy it.”

Legislation on which 1000 Friends has taken a leadership role in advocating in favor of — including legislation to allow accessory dwelling units and “middle” housing in most neighborhoods — helps break down the economic and racial separations institutionalized in the development patterns of many of our towns and cities, allowing all Oregonians access to opportunity.

It’s time to re-think what makes a “family” dwelling. The legislation we have supported provides housing opportunities to match the family size and incomes of most Oregonians - duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, and cottage clusters in neighborhoods where detached, single-family housing is also allowed, near the things we all need to easily access, like schools, stores, parks and other amenities.

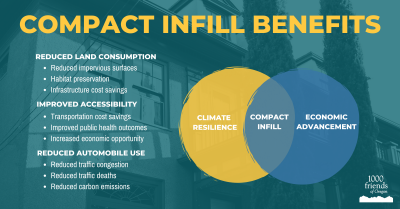

The bottom line is that compact infill is better for the climate, our health and the economic health of our communities.

CLIMATE BENEFITS

More diverse and compact housing choices makes a significant contribution to addressing climate in at least two ways: reducing greenhouse gas emissions and providing more opportunities for capturing carbon.

“A typical two-adult family that locates in a walkable urban neighborhood uses far less land (10-30 units per acre, compared with 2-6 in suburbs), owns one rather than two vehicles, and makes half as many vehicle trips as they would in an automobile-oriented suburb. Consumer surveys indicate that a majority of households would prefer to live in a compact house in a walkable urban neighborhood than in sprawled, automobile-dependent areas. The table below lists some of the resulting benefits.”

PUBLIC HEALTH BENEFITS

Leading public health journal Health Affairs states that “There is strong evidence characterizing housing’s relationship to health. Housing stability, quality, safety, and affordability all affect health outcomes, as do physical and social characteristics of neighborhoods.”

The link between public health and housing is clear, and the more energy we invest as a state to ensure we’re meeting the housing needs of all Oregonians — in existing neighborhoods — the better future we’ll create as a result. Housing extends far beyond a physical place to call home, it has significant effects on mental and physical health, educational and economic outcomes and so much more. Supporting and funding policies that allow for compact infill means supporting the best-possible future for Oregon.

ECONOMIC HEALTH of COMMUNITIES

More compact development saves public dollars on infrastructure; pipes, roads, public safety and more. Oregon’s infrastructure is a physical and fiscal investment in the future of its residents and communities.

Some development patterns create much higher public costs than others. Land-extensive sprawl costs far more for infrastructure than more efficient, compact development – especially when total lifecycle costs are included in operation and maintenance. Greater separation and longer distances in sprawl — typical of exclusively detached single-family areas — requires costly roads, sewer and water lines. Services feel the squeeze too, spreading thinner to serve fewer people.

In contrast, more compact growth directs development into existing communities and creates walkable neighborhoods with mixed land uses and transportation options. At the same time, it saves communities millions.