By Brett Morgan

If you haven’t heard of the “Interstate Bridge Replacement” (IBR) Project on Interstate 5, you likely know it by its former name, the Columbia River Crossing, or CRC. While it has a long history, the CRC debate fell apart in 2014, after 8 years and almost $200 million in studies, planning and acrimonious debate. 1000 Friends of Oregon was at the heart of the fight against CRC, including when Robert Liberty served as the Executive Director of 1000 Friends of Oregon.

The IBR project is the new name for the same CRC bridge project that the region already rejected once. Now that same project has a new name but is setting out on the same exact course as the first project, spending $3 to $5 billion in tax dollars to widen I-5 to sixteen lanes in places, mainly to save commuters from Vancouver a few minutes of car travel time.

Equity is critical and not in the picture

From an equity perspective, the IBR provides the most congestion relief to the commuters in Ridgefield, a lower-density, high-income and predominantly white community north of Vancouver.

Portland’s thriving Black community was wiped out by the construction of I-5 and other “urban renewal” projects. Addressing the racist impact of this displacement in this project is critical, and consistent with the Biden Administration's commitment to taking an equity-focused look at the U.S. interstate highway system. A system that has and continues to exacerbate inequalities in wealth, health, and safety regarding people of color — particularly Black communities.

The IBR project does nothing to address this legacy. Rather than invest in something truly transformational for our region, ODOT is proposing a freeway project right out of the last century, which will lead to the same outcomes: increasing greenhouse gas emissions and adverse impacts on Black, brown, and low-income communities by physically dividing neighborhoods, destroying wealth, and polluting air. More recent examples can serve as a forecast of what the IBR would do. To the south, ODOT has grossly mishandled the Rose Quarter Project, with its even more direct ties to Portland’s Black community. The botched project created many problems, including intentionally creating wedge issues in Portland’s Black community, disbanding community advisory panels, hiding an entire lane of highway expansion in their design documents, a woke-washing PR campaign, and cost overruns.

Climate change isn’t a consideration

The IBR also fails from a climate change perspective. Widening I-5 to 16 lanes (including all the ramps, merge lanes, etc.) to facilitate more driving to the outer suburbs in Washington will make the climate crisis worse. In Oregon, 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions come from our transportation system.

The car-centric project ODOT is putting forward will actually move Oregon backward on creating a climate-smart transportation system. Juxtapose the IBR next to the clean energy bill Governor Kate Brown just signed — touted as “one of the most ambitious in the country” — and you can see the astounding amount of coginitive dissonance needed to justify the project.

Adding lanes won’t make the commute easier or faster for drivers — widening highways induces more demand, and in the long term generates more congestion and emissions. It also seems that leaders on both sides of the river feel strongly, and very differently, about whether to include public transit, with no consensus on either light rail or bus rapid transit.

Regardless of how effective, sustainable, and accessible public transit that connects Portland and Vancouver needs to be one of the top priorities for the bridge to address climate change.

The costs are driven by highway expansion

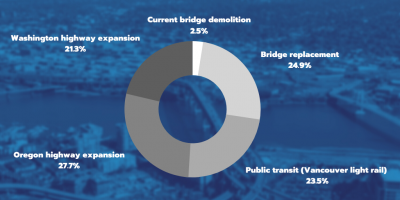

The 2014 CRC project was estimated to cost $3.6 billion, $90 million of which was to destroy the old (and current) bridge. The bridge replacement itself would cost $900 million, and $850 million was earmarked to add public transit (light rail) to Vancouver.

Roadway investments unrelated to the bridge replacement made up almost half of the remaining project costs, with highway expansion spending on the Oregon side totaling $1 billion, and the Washington side adding an additional $770 million.

We know much of the new IBR project will follow this same template of negligent spending because both state transportation departments are insisting that local officials use the technical documents from 2014. While some argue there is a need to move quickly to secure federal funding, moving quickly means relying on the old federal documentation, even if those documents make no mention of climate change or racial equity. This is a false sense of urgency that would shackle our region to the same outcomes we already rejected in 2014.

A better alternative exists

There are many cheaper, smarter, greener, and more equitable alternatives to the project’s current path, including an integrated approach that combines a supplemental bridge with congestion pricing, transit improvements, and changes to land use policy.

1000 Friends of Oregon led the effort to find a smarter alternative to the proposed Western Bypass in the 1990s, which recognized that land use and transportation are two sides of the same coin: for either to work effectively and serve all, they must be integrated. Yet it seems that lesson was never learned by ODOT. In Oregon, the Metro Council, the City of Portland, the Legislature, and TriMet all have independent authority over the project; if they insist on a better alternative, the IBR cannot be built.

In May of this year, David Bragdon, who was Metro Council President when the CRC was approved, wrote a scathing critique of the decision-making that led to the CRC and now the IBR. Bragdon says: “I’m saddened to see that almost a decade later the Governors of Oregon and Washington have unleashed the same agencies again to use the same techniques and simply continue this stupefying track record of incompetence and dishonesty.”

He concludes his commentary with this reflection: “ODOT and [Washington State Department of Transportation] take one truth, and then extrapolate many untruths from it. ‘We need to do something to fix the problems in this corridor,’ is true, but ‘Therefore we need to do the most expensive, stupid something’ is not true.”

Oregonians deserve better from ODOT and our state leaders.

Robert Liberty served on the Metro Council while the CRC was debated and served as the Executive Director for 1000 Friends of Oregon from 1994 to 2002.

Brett Morgan works as 1000 Friends of Oregon’s Great Communities Policy Manager and focuses much of his work on creating a just, sustainable, and accessible transportation system.