By Devin Kesner | 7-minute read

In rural Washington County, a 15-acre diversified vegetable farm grows more than a hundred crops: cabbage, potatoes, peppers – so many types of produce that from above, the mass of planting rows resemble a multicolor rag rug. The land abuts a railroad, separated from the farm by a thin gravel lane, where weathered homemade signs advertise gopher removal services and hay sales alongside the farm’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). The operation, Stoneboat Farm, is less than five minutes by car from the nearest city (a little longer when farm equipment shares the road), but feels distinctly unencumbered by urban life. Residents hope it stays that way, and Stoneboat founder Aaron Nichols is helping lead the effort.

When Aaron learned about the city of North Plains’ proposal to expand onto nearby prime farmland for mostly industrial development, he already had a network of hundreds of community members who he knew would personally understand what was at stake. He sent out an email to some of the 750 families who receive produce as a part of the farm’s year-round CSA, asking for their testimony on why they valued the agricultural lands that the city’s plan threatened. He also submitted his own testimony, showed up to public hearings, and even formed an organization dedicated to farmland protection – all while still managing the farm and its 10 employees.

“The public presence of a local farm can be central to a community and make a difference beyond food.” —Aaron Nichols

Stoneboat sits one farm away from the expansion area and spotlights the stakes of cities seeking more land for the wrong reasons, building out rather than up. The farm runs one of the biggest CSAs in the state and provides food security and habitat protection for the immediate community, including North Plains. It brings people together through their appreciation of local agriculture – community connections form around the farm as folks share recipes, stories, and news. As Aaron puts it, “The public presence of a local farm can be central to a community and make a difference beyond food.”

Aaron and his team manage the farm using sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices that build organic matter, provide habitat for pollinators, combat climate change, and prevent erosion. Storey Creek interrupts his rows of crops, creating a native plant corridor and important habitat for birds, wildlife, and insects. In addition to its market production, the farm devotes three acres to the Campo Collective, a nonprofit cooperative farm model and farmer-training program for beginning farmers whose first language is Spanish. The Campo Collective provides food to free-meals programs, restaurants, and communities facing hunger and food insecurity.

Stoneboat is safe from the North Plains expansion effort – for now – because it lies within what are known as rural reserves, a legal designation that, among other things, means that land cannot be developed for another 40 years. But, without that land use protection, the farm would likely be facing intense pressure to develop due to the farm’s proximity to the Metro and North Plains urban growth boundaries, also called UGBs. (The farm is about two miles from Metro’s UGB near Hillsboro, which is also in the process of seeking a boundary expansion.)

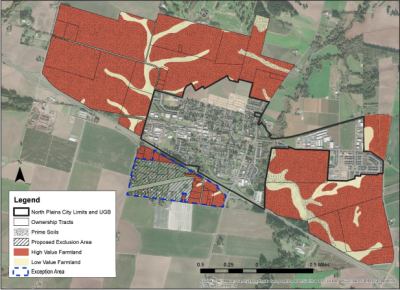

The North Plains land grab

The plan to more than double the size of North Plains, which currently reaches about a mile from Stoneboat, brought Aaron to action. A single increase of this magnitude to a city’s boundaries is unprecedented in Oregon, and most of the expansion would be for industrial and commercial use, with only about 167 acres set aside for housing. While cities normally need to prioritize expanding onto non-resource lands or lands with lower-quality soils when proposing a UGB expansion, North Plains is surrounded almost exclusively by high-value farmland and prime soils. This means that any expansion would almost certainly pave over some of the best soils in the state and raises the ethical bar for proving that the expansion is what’s best for the greater community.

Only about 16 percent of Oregon (excluding federal lands) consists of high-value soils, and only about 4 percent is prime farmland. Almost anything climate-appropriate can be grown on prime soils with minimal inputs, which means the land needs fewer things like fertilizer, soil amendments, and irrigation. On these soils, in just 10 years Aaron has been able to transform what was formerly a rundown nursery on compacted soil, growing only thistles, into the bustling food producer and community connector it is today. Compared with other places he has farmed with much lower-quality soils, Aaron says, “The difference has made me see that, as farmers, the most we can hope for is to live up to the potential of our soils, and we, in many parts of the Willamette Valley, are blessed with world-class soils.”

Like all soils formed by ancient glacial melt, the soils surrounding North Plains and underlying Stoneboat Farm are impossible to replace or reproduce, particularly once they are buried under concrete and steel. Oregon’s land use system recognizes this, aiming to preserve our limited supply of agricultural land in order to conserve economic resources, maintain our agricultural economy, and ensure our communities have enough nutritious food. Yet piecemeal expansion proposals can easily pave over these values in the name of other industries or luxury housing (which, by the way, is the opposite of the housing we need).

“The difference has made me see that, as farmers, the most we can hope for is to live up to the potential of our soils, and we, in many parts of the Willamette Valley, are blessed with world-class soils.” —Aaron Nichols

As the possibility of expanding the city grows, deep-pocketed developers try to get ahead by purchasing land without a real plan, in the hope that the land will become buildable. This practice, called speculation, raises already high farmland prices, closing out the possibility for farmers to purchase or lease additional land for farming. Beginning farmers who would become part of the interwoven regional agricultural network would be priced out. Prime areas for farming then become unavailable to farms like Stoneboat looking to expand.

Aaron is already witnessing these trends in real time. Even though demand for local food is growing at a record rate and skilled farmers are looking for land, no new farmers have moved in around him, Aaron says. He attributes this to high land prices that don’t reflect agricultural value, like a nearby 80-acre property with no water rights and no house that was recently listed at $7 million. At that price tag, the grass seed currently being grown on the property seems to be merely a placeholder for a data center or a warehouse.

A false choice between livable cities and thriving farms

The UGB has become a target in debates over how to solve the housing crisis and promote economic development. Bills from recent legislative sessions exemplify the ways in which the UGB has been centered in political debates.

Senate Bill 4 passed in 2023 with a provision allowing the governor to designate lands outside UGBs for the tech sector’s semiconductor industrial uses, bypassing the usual land use processes. (A year later, the governor has not needed to use this authority, because sufficient industrial land already exists within UGBs.) And this year’s SB 1537, Governor Kotek’s housing sprawl bill, passed following the failure of a similar bill last year. The new law allows cities to sidestep land use laws for a one-time exemption to expand their boundaries by 50 to 100 net residential acres, with very few housing affordability requirements baked in and ignoring the fact that for truly affordable housing, we must invest in infrastructure and remove barriers in existing UGBs.

Proponents of these measures often minimize what is lost when a city seeks to expand its boundaries. The land outside a UGB is not just flat, vacant, developable land. It isn’t primed and ready for affordable housing locked away behind a stubborn, invisible legal barrier. In many cases, the land outside the UGB is working land, supporting the livelihoods of farmers or ranchers and their employees, providing food security for the local community, and protecting wildlife and ecosystems. These lands alone contribute to a $33.3-billion industry – Oregon’s number-two industry, in fact – responsible for more than 15 percent of Oregon’s economy and more than 20 percent of our jobs.

Stoneboat Farm’s battles against sprawl to preserve agricultural land and livelihood highlight what we risk when we deprioritize farmland. Too much is at stake for us to casually – permanently – pave it with UGB expansions. Our farming economy, food systems, and everyone feeling the burden of the housing crisis deserve for us to first address affordable housing and economic needs within current UGBs before sprawling out.